What happened in thirty five years that we, if judged by what’s shown on television today, became a generation of nit-picking dimwits? The women, once seen as one another’s unrelenting support system, became gaggles of angry hens, aimlessly fighting over one thing or the other, usually the rooster. The men, long ago pillars of suave strength and dignity, got reduced from role models to characters you wouldn’t want to get stuck in a dark alley with. The stories that used to be inspirational tales of human emotion, relation, life and survival, deflated into a wet mess of disintegrated quicksand. We watch dramas these days, and get stuck in their twisted little tales, but it’s usually with anguish and not anticipation. The exceptions are few, and far between.

PTV recently brought back the 1985 classic, Tanhaiyan, written by Haseena Moin, directed by Shehzad Khalil and featuring Shahnaz Sheikh, Marina Khan, Asif Raza Mir, Badar Khalil, Qazi Wajid, Behroze Sabzwari and irreplaceable others in roles that were lovable and unforgettable. One watched Zara and Sania regain control of their lives after their parents’ untimely death and how the unbreakable sister bond extended to Aani, their aunt, who became their support system. Zara had emotional issues but she managed to stand on her own feet and achieve what she had set out to. Zain’s selfless love for Zara needed no words; that intent gaze said more than words ever could. The chemistry was so intense that we knew he loved her the minute he called out her name in the stairway; it was in the last episode in which he realized and acknowledged that love. Their guarded romance was swoonsville, leaving every woman fantasizing about having a man like Zain. There was uncontrollable laughter whenever Kutubuddin came on screen with that delightfully lilted sidestep; albeit a supporting character, it was his comic monologue that brought Zara out of her comatose condition after her accident. Every character counted.

Behroze Sabzwari as Kutubuddin didn’t just provide comic relief. He was an essential part of the story.

Aani, for example, etched perfectly by Badar Khalil, was a dynamo. She had short hair and an iron will. She lived alone and took her nieces under her protective wing when their parents died. She couldn’t cook or draw up a domestic budget but she was ethically upright and forward thinking. I’ve been watching a lot of local television and can’t think of a single character that amounts to the impression Aani made.

I revisited all 13 episodes of Tanhaiyan and wondered how it would have panned out had it been written in 2020, by one of our ‘modern writers’ (which I say with disdain as there is nothing modern about the way most of them write).

For starters, it would be titled, Ishq Main Tanhaiyi as to immediately draw attention to a possible sob story.

Zara and Sania’s parents would surely have died in the first three episodes but the similarities would have ended there. The girls would be taken in by Aani, a poor and destitute aunt, who’d be supporting an ailing husband by stitching clothes on her manual Singer sewing machine. They’d live in Hyderabad and Aani would already have a couple of obnoxious children, making sure Zara and Sania were made to feel unwelcome.

Zain would make an entry like a knight in shining armour but he’d be a cousin, not a friend. And while he’d be possessively in love with Zara, we’d see Sania secretly lusting after him, because no modern drama is complete without that sickening sister rivalry we see these days. Aani would have a landlord, Faran, who’d have the hots for Zara and we’d witness some form of sexual harassment or abuse come into play. His aunt, Apa Begum, would want Faran to settle down with Zara, who could bear him a string of strong and robust man cubs. Apa Begum would propose to wed Zara to the aging and by no means cute Faran (Qazi Wajid was adorable) by wavering off Aani’s rent. Oh, and Ishq Main Tanhaiyi would have a Kutub ud Din, but he’d be Aani’s 16 year old bratty son, who’d have a crush on Sania.

Somewhere in the story we’d witness a miscarriage, possibly Aani’s as she would have to slip and fall while performing some heavy duty chores; anything to add to the misery. Let’s not forget the necessity of a wedding and a controversial wedding night, because again, we need that kind of thrill without crossing the line. We’d call it a platonic marriage if we could. Zara and Sania would definitely visit a shrine at least once after each tragedy. Oh, and a slap or two would be inevitable, because no modern Pakistani drama is complete without it.

Badar Khalil as Aani, the irreplaceable khala

At this point Hasina Moin would sue the modern writer for wrecking her original story and causing emotional and psychological damages.

What the hell happened in 35 years?

“Literature adds to reality, it does not simply describe it. It enriches the necessary competencies that daily life requires and provides; and in this respect, it irrigates the deserts that our lives have already become.†~ C.S. Lewis, a British scholar and novelist

Tanhaiyan was telecast during the Zia era, when writers like Hasina Moin felt the need to tell stories to counter the narrative that was being written for them. Literature of that time was, as it should be, transgressional. Somewhere down the road, with the introduction of multiple channels, dramas became less about thought-provoking literature, and more about volume and ratings.

The entertainment industry mushroomed with countless pools of writers, directors and actors and massive budgets signed off by production houses, but they couldn’t create a single Tanhaiyan, Aangan Terrha, Ankahior Dhoop Kinarey because creating classics was no longer the objective. Humsafar came close but its success fed on the Fawad Khan – Mahira Khan chemistry and not a particularly inspirational story. Humsafar, for all its glory, was still the story of a girl struggling with personal tragedy, class difference and ultimately, a jealous husband who couldn’t trust her.

Instead of giving viewers something to dream and aspire about, or better still, think about, productions nowadays have taken the easy route of giving people an overdramatized version of what they are already watching on the news; that’s what gets them the highest ratings therefore the highest ad revenue. Producers want to make stories that sell, not stories that force people to think. But art or literature is ideally supposed to raise the collective mass consciousness to a level of heightened intellect. It is supposed to challenge, not conform.

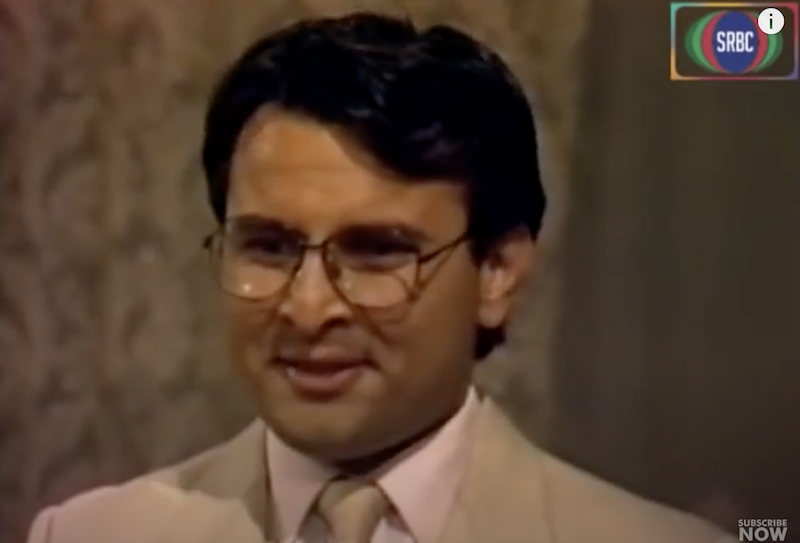

Asif Raza Mir played Zain, whose selfless love for Zara needed no words; that intent gaze said more than words ever could.

Domestic abuse, social issues including rape, acid attacks, misogyny, vani, child marriages and pedophilia, the exaggerated arena of domestic politics and intrigues, pitching the girl and her in-laws in opposing and very destructive corners. This is the modern Pakistani drama, where class differences lay the premise to almost every typical story. It builds upon jealous and petty men, sister rivalry, internal intrigues, domestic violence propagated as a norm, senseless pregnancies and miscarriages and many other similar elements that serve no great purpose beyond sensationalizing the story. Dramas that stand out are few and far between.

It’s not that social awareness was not part of storytelling back in the eighties; it was and crime was just as much a part of life then, as it is now. Drama serials like Waris, Khuda Ki Basti and even the seemingly innocent programs like Alif Noon and Fifty Fifty or even Aangan Terrha, were deeply political. But somewhere in three decades, the responsibility of telling stories shifted from well-read and intellectual writers like Hasina Moin, Anwer Maqsood, Amjad Islam Amjad, Kamal Ahmad Rizvi and others, to writers who are obviously not as nuanced or literate. Back in the eighties we’d have one drama a day, from different TV stations (Karachi, Lahore, Islamabad, Peshawer and Quetta), and telecast on the state channel, PTV. There was time to write, create, direct and produce with care and precision. There was time and desire to create classics.

People around the 80s remember the process: The writer, in Tanhaiyaan’s case Hasina Moin, would write a story and then brainstorm its execution with the director, in her case usually Shehzad Khalil. Casting would be done, followed by readings and rehearsals before the actual drama shoot went on floors. These days the cast doesn’t even always have the full script before they arrive for shooting. Casting is done accordingly to popularity of the actor. Scripts are rewritten, changes made at the last minute. A drama serial written as 24 episodes will most certainly be extended with flashbacks and dream sequences, to 30 episodes at least. The PTV format of a serial being 13 episodes long was, like the dramas it presented, just as classic.

The world has already come to a standstill, thanks to the coronavirus pandemic, and this wouldn’t be a bad time for producers and their pools of creative heads to also slow down, stop and think.

- This article was first published in Instep on Sunday, April 26 2010