In many ways, Saim Sadiq’s journey to Cannes started long before the genesis of Joyland. The director’s fascination with films was apparent from a very young age. A three-year-old Saim would demand to be dropped off at his aunt’s house so he could watch Sridevi’s Laadla on her VHS player. “Every day I would watch Laadla,” he laughs now, “It’s an obnoxiously bad film but it’s so entertaining and I loved Sridevi, God bless her.”

This went on for months, Laadla eventually being replaced with other films, but always from Bollywood. “My parents would drop me to my aunt’s house and I would be totally fine, a three-year-old kid not caring at all where his parents were because I was watching Sridevi and Anil Kapoor, or Shahrukh and Kajol.”

Bollywood remained Saim’s primary source of cinema for most of his younger years, his “childhood love” as he calls it. With the advent of the internet and DVD technology, Saim says his “world opened up”. He began to read about films as voraciously as he watched them and this directed his attention towards international cinema. He’d go to the DVD store and ask for films from Sweden, Iran, and Poland. For a teenage Saim, films were gateways to different ideas and ways of living. “I also felt the most comfortable in my own skin while engaging with cinema,” says Saim, “Whether it was watching a movie, or reading about a movie, or writing about one. I was the happiest at that point.”

The filmmaker also had a knack for storytelling from a very young age. “I remember being a writer since I was a child,” he says. “It was inherent to me”. However, for a very long time he didn’t see how connected filmmaking and storytelling are. “Those things conflated for me much later, in LUMS,” he remembers now. “Eventually I realized I can write, I’m interested in movies, and I can take pictures, and these things are connected so perhaps I’m meant to be making films.”

Saim at the Cannes Film Festival’s award ceremony

By this time, Saim was no stranger to the camera. His first video project had been a music video when he was in high school. During his undergraduate year at LUMS, he also worked on short films and documentaries. At the end of his four years at university, as Saim’s batchmates went off to work at corporate jobs, Saim simply didn’t. Instead, he told his parents that he had found a way to contact Sarmad Khoosat and would be working with him. At that point, all Saim knew of Sarmad was that he had made Humsafar, which his parents loved. The bluff manifested into reality because Saim did find a way to contact Sarmad, who eventually brought him on as the assistant director on Mor Mahal.

Saim knew within his first day on Mor Mahal that he belonged on a film set. “I’m the happiest on a set,” he says, “I’m so comfortable. Things that I find difficult to do otherwise, if you ask me to do them on set, I’ll do them easily. I’m tired, I look terrible, I don’t eat well or sleep enough, but none of it matters because I enjoy it so much.”

On set, Saim also discovered a side of himself that he liked, “I became a nicer version of myself,” he reveals, “It was much more difficult to irritate me, I would not shout at people. I was the kind of AD who was nice but would get things done. I realized this is the best version of me, the person I am on a film set, so it made sense for me to do this with my life.”

It was while shooting for Mor Mahal that Saim was admitted for a Masters in Columbia University’s film program. Two weeks before filming for Mor Mahal wrapped, Saim was flying to New York to begin a formal education in filmmaking. The next few years were, “the best thing that ever happened to me,” he says.

It was during his time at Columbia that Saim first sat down to start giving form to an idea that had been swirling around in his brain, an idea that would eventually become Joyland.

Saim with Joyland producer Apoorva Guru Charan

In the month leading up to Joyland’s premiere at the Festival De Cannes, Saim Sadiq says he started, “losing my mind a little bit. And not in a cute way”. The director had been carrying his feature film for the better part of a decade. For at least six years, he had been actively writing it, evolving the story, letting the characters grow in the directions that they were moving in. The idea, however loose it was at first, had been with him for much longer.

To Saim, Joyland was very much like his child, he admits. It had been incubating inside his mind for a very long time and, as the premiere approached, he found himself faced with the reality that it was no longer his to carry. Coupled with the stress of finishing postproduction, this was “very emotional” for the filmmaker, and straight up, “awful”. However, there was nothing to do at that point other than power through and two days before the festival, Joyland was ready to meet the world.

On 28th March 2021, less than a year after he finished filming Joyland, Saim Sadiq turned thirty-one. At 2:00 in the afternoon, he sat contemplating whether to go take a shower. An email arrived in his inbox. It was from the head of programming at the Festival De Cannes.

Saim still had about two weeks of editing to go before Joyland would be ready for color-grading. With the encouragement of his producers Sarmad Khoosat and Apoorva Guru Charan, he had decided to submit the film for consideration. There was an expectation that they might not get in with an unfinished cut. This expectation, as we now know, was unfounded. Cannes was emailing Saim to inform him that Joyland had been picked as a contender in the festival’s Un Certain Regard section.

View this post on Instagram

What followed was a rush of postproduction in Los Angeles, one flight to France with two DCPs in hand, forty members of cast and crew reuniting in a place they never dreamt of and, finally, a cinema filled with a thousand people, all gathered to watch the first ever Pakistani feature film to make it to Cannes.

Folks in Pakistan watched keenly as social media posts showed Saim with his producers, crew, and cast — Alina Khan, Ali Junejo, Sania Saeed, Sarwat Gillani, and Rasti Farooq to name a few — posing on the red carpet in their elaborate ensembles. On the day of the premiere, we felt rising anticipation as the Joyland party posted live updates. When the screening started, their social media went silent and we waited eagerly to know how it went.

Three hours later, we were taken into the cinema: Saim holding back tears, everyone exchanging hugs, and the hall echoing with clapping from what’s said to be the longest standing ovation ever seen at Cannes. History had been made, a moment forever ingrained in the collective memory of Pakistani culture and Saim was at the center of it.

Before it was anything else, Joyland was about Saim and his family. “Not in a direct way, it’s not like I’m a character in the film,” he clarifies. “It’s not like my family are characters in the film. But just observationally, it came from the things that moved me in relation to a certain amount of gender politics that exists around us.”

At first, all Saim knew about the story was that it unfolded around three main characters. “I didn’t know how it will develop,” he says, “But at the center of the film there was always a man, a woman, and a transperson, from the very beginning.”

View this post on Instagram

It was important for Saim to include a transperson in his story because he wanted to explore gender. But the director asserts that Joyland is not a film about a trans woman. It’s an ensemble film, he explains, and Biba is a character who just happens to be trans. She is as important as the other characters, no more, no less. Saim put her in the story because his aim was always to show a holistic perspective on what social rules are for different people. “I didn’t feel the need to make the whole film about her transness just because she’s in the film. She’s in the film because she should be, just in the way that cis women and men exist in films.”

Even during this interview, it’s clear that storytelling comes naturally to Saim. He speaks with a quick eloquence, is never at a loss for the right words, drawing his listener in with animated expressions and hand gestures. One day, Saim recalls, he was telling a close acquaintance about this idea for a feature with these three unformed characters. The person told him to meet with Nagma Gogi, a trans woman who has been singing and dancing around Pakistan for decades.

It was during his conversation with Nagma, that the world of Joyland began to emerge in Saim’s mind. “She told me her life story,” he remembers, “That conversation was a big motivator. She would bring songs into her story and start singing them. I was just enamored by her way of storytelling and realized there’s something about the ethos of what she was telling me that I liked a lot.”

What was ignited by Nagma’s story eventually formed into the space within which Joyland unfolded: the world of the mujra (erotic dancing) theatre. Unlike Saim’s award-winning short film Darling, Joyland is not about the theatre but uses it as a site of storytelling. Saim admits that he finds Pakistan’s mujra culture “endlessly fascinating”.

Saim at the Cannes photocall with Sania Saeed, Ali Junejo, and Alina Khan

“It makes no sense that this is a thing that us Pakistanis came up with, that this is our own original creation, this brand of erotic dancing,” says Saim. “That this is the country where a woman can go on stage and mock the men who are sitting in the aisles and they will have to laugh.”

When Saim spoke to mujra dancers, he found that many of them found their profession to be empowering in some ways. “The women can get on stage and subvert gender dynamics, they’re the ones in control of their sexuality, they’re the ones in power,” he reveals. “There’s a glee that they feel when they go on stage.”

The filmmaker found it particularly interesting that these shows are subject to censoring much like movies and television. Censor board representatives visit the theatres and approve dance routines for audiences. Saim laughs as he recalls how dancers fight with the censor board for “every odd step”. “The censor board will tell them to take a step out, that they can’t put their hands on their butts for three seconds, that they must cut it down to one second,” he chuckles.

As he conducted his research, the world of mujra theatres began to reveal itself to Saim. “These men sit and take whatever power play is happening with the dancer. Then they step back into the outside world and regain that power. The existence of this as a means of entertainment for men who are otherwise very conservative is so fascinating. It’s the contradiction that we don’t want to talk about, that we don’t want to own, and our country is full of these odd contradictions.”

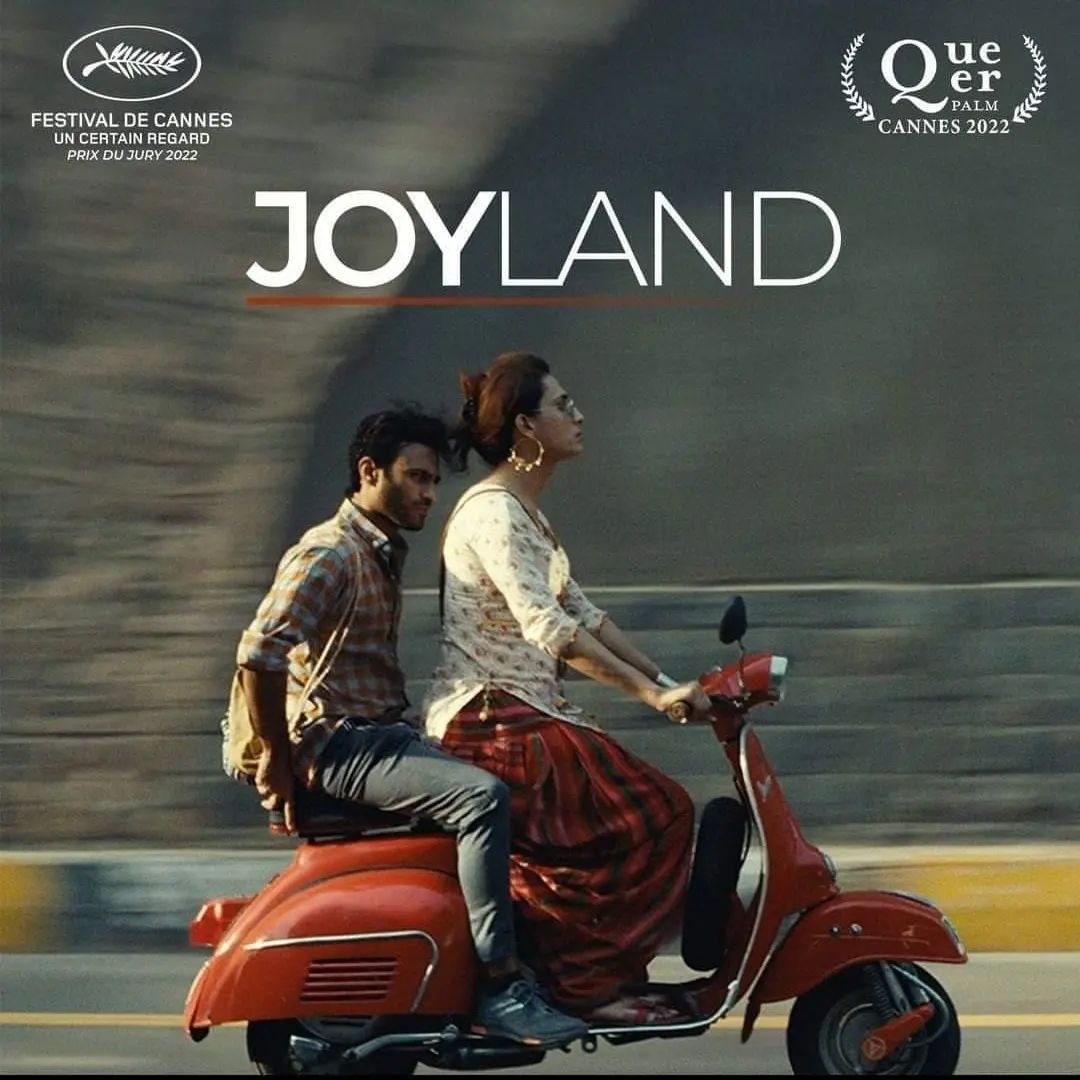

A poster showing Bibi (Alina Khan) and Haider (Ali Junejo)

In 2015, Saim started writing Joyland. His relationship with writing is more of a mixed bag than filming. “It’s very lonely,” he says, “You’re sitting in a room with a screen staring back at you. You think you’ve written something great, two days later it seems terrible.” Nevertheless, Joyland was the story that came to Saim the easiest. “There were highs also which were very very exciting.”

Between the first draft of Joyland and its shoot last year, Saim made Darling and completed several other projects at Columbia. Without funding and a crew, he found himself with ample time to keep tweaking the story and produced several drafts.

In 2018, after the release of Darling, Saim and Apoorva got to work on making Joyland a reality. After three years of preproduction – finishing the script, securing funding, and putting together a cast and crew – Saim called action in Lahore on 24th September 2021. Less than a year later, he was carrying DCPs of the film on a flight to Cannes.

The feelings that were threatening to overwhelm Saim during postproduction subsided within the sheer scale of the machinery that is the Festival De Cannes. There was a tech rehearsal to do, a photocall to dress up for, followed by a red carpet appearance. All of this passed in a whirlwind and then came the day of Joyland’s premiere. “The premiere was beautiful,” Saim beams, “Everybody had arrived by then, we were all rested enough, everybody looked cute.”

Members of Joyland’s cast and crew at the film’s premiere

Most importantly, everybody was together again. “I don’t know if everyone who was on set ever thought we’d meet each other again, all of us in the same space. We also knew that probably that is not going to happen again. The film will screen in other countries, but most of the crew won’t be going there, maybe the cast but sometimes not even so.”

During the tech rehearsal, Saim had been prepared by Cannes officials for an inevitable reality: in a cinema full of 1,200 seats, people get up. They could go for bathroom breaks, or just to get water, but it’s not possible to keep so many people in their seats for two hours. Saim was told not to take this heart or see this as a judgement on his film. So for the first hour of Joyland’s screening, Saim was watching the audience more than he was watching the film.

Hyper aware of movements and sounds coming from the audience, he waited for people to get up. No one did. The first person who did go to the bathroom was his lead actor Ali Junejo. The second was Alina Khan who plays Biba. The third person was the editor of the film. When he heard people laughing to the moments of humor dropped into Joyland’s first half, Saim was able to relax and actually watch the film.

When the screen cut to black and credits started roll, Saim became aware that the cinema was filled with clapping. He couldn’t see any of it, however, because he’d asked for the lights to remain off until the end of the credits – he wanted all of the crew’s names to appear on screen. This was an admirable decision but one that Saim suddenly regretted when he realized that he was missing an ovation.

Fortunately, someone from the festival’s team read the situation and turned on the lights. The whole cinema stood clapping. “It was quite magical,” recalls Saim. “We didn’t expect the ovation would be so long. Everybody just started hugging each other, for like ten minutes we were all going around hugging each other,” he laughs.

View this post on Instagram

Joyland’s premiere is the one part of Cannes that Saim feels he was able to be truly present for and experience completely. “I was feeling so many things,” he says, “I was so aware and I was feeling like I’m being so tacky, crying at the end of my own film. I couldn’t stop so I was making odd faces to hide it but then I saw that everybody was crying so I just went with it.”

The high of Joyland’s premiere was followed by a crashing low. Saim fell sick. Too sick, in fact, to attend the festival’s concluding award ceremony. When Apoorva called the festival officials to inform them of this, they stated that he had to be there. The team knew then that they were winning an award. What they weren’t expecting were two awards. Joyland won the Jury Prize in Un Certain Regard and the Queer Palm.

On his return to Pakistan, Saim mostly slept. “I sleep at odd hours and I sleep for far too long,” he laughs. Every chance he gets, the filmmaker thinks about new ideas. It’s important to him to have a new idea to be excited about.

Saim on the set of Joyland in Lahore

In a lot of ways, however, Saim still carries Joyland with him. The film still needs to be released in Pakistan — Saim stresses that Joyland was made for local audiences. Distributors need to be locked down for other countries, posters need to be designed and there are trailers to make.

“I still think about the film, but in a different way,” says Saim, “I think about it as a thing that already exists. I can’t change it or add to it so I can’t think of it like a caretaker. Which is a big difference.”