Having won various accolades internationally, the short-documentary film Indus Blues was premiered for a Pakistani audience at the 10th Karachi Literature Festival [KLF] last weekend. Directed by Jawad Sharif and produced by Sufi singer Arieb Azhar, the documentary encapsulates the dying heritage of Pakistan; folk music and the last of traditional instrumentalists and crafters who are an asset to the country, though not valued.

Travelling through the Indus, Jawad and Arieb spend five years on this project which sheds light on the rich, however, undervalued musical culture of our country. Featuring some of the most celebrated and talented folk artisans, the thought-provoking film demands the viewers’ attention in order to take measures to preserve the musical richness while they still can.

Read:Â Indus Blues trailer explores the dying music heritage in Pakistan

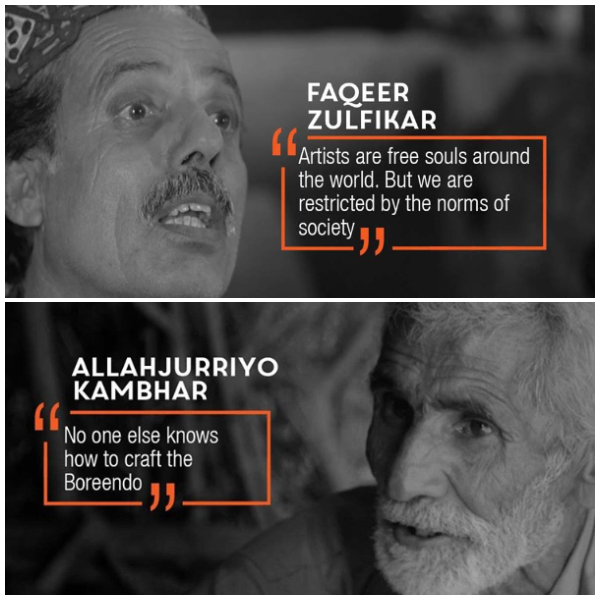

Starting from Sindh, the filmmakers have travelled throughout the province to find some of the most unique stories about craftsmen and their instruments. The film begins with the archaeological site of Moenjodaro and introduces the only Boreendo player of Sindh, Faqeer Zulfiqar, who also plays the Sindhi variant of flute called ‘Narr’. Boreendo is made out of clay just like a clay pot with small holes in it which enable the player to control the pitch of the sound. Allahjurriyo Kambhar is the last craftsman for this instrument in Pakistan and continues to live in hardship.

Top: Borendo player, Botton: Borendo craftsman

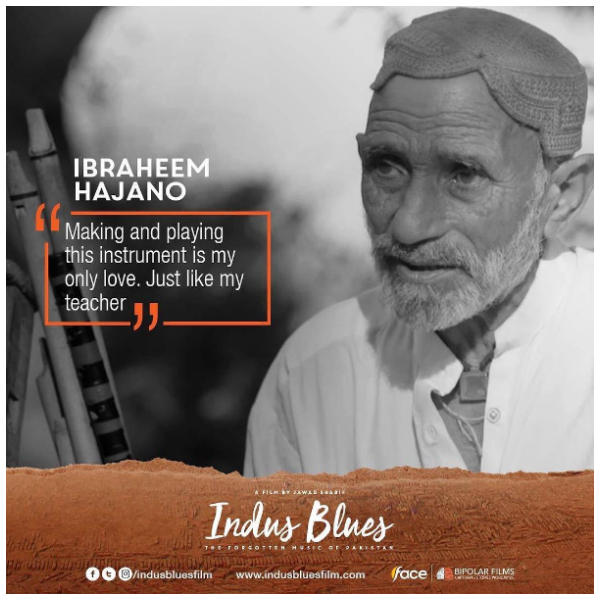

The narrative moves on to Goth Khamisu Khan, a village where Abdul Khamisu Khan resided who was the original crafter of Alghoza. He taught his student Ibraheem Hanejo the art of crafting this instrument and he is now the only man in Pakistan who knows how to create the masterpiece. There’s no demand for the instrument in today’s time so, he only makes it for his teacher’s son Akbar Khamisu Khan who is the last Alghoza player. Ibraheem has dedicated his life to the creation of this instrument.

Alghoza craftsman, Goth Khamisu Khan

The largest district of Sindh, Thar is home to some of the most exceptionally talented instrumentalist and singers, Mai Dhai being one of them. Sattar Jogi from Umerkot, who bears the sole responsibility of keeping the cultural music alive, is a snake charmer and a ‘Murli Been’ player. As the instrument is not sold publicly, this heritage symbol of Thar is slowly but gradually fading away. “Newborns are made to drink a small amount of snake poison for a few days and for this duration they do not drink the mother’s milk. If the baby survives, he/she is considered a Murli, if not, then he belongs to God,” Sattar Jogi revealed while talking about how a person becomes part of the tribe.

Murli Been player from Umerkot, Thar

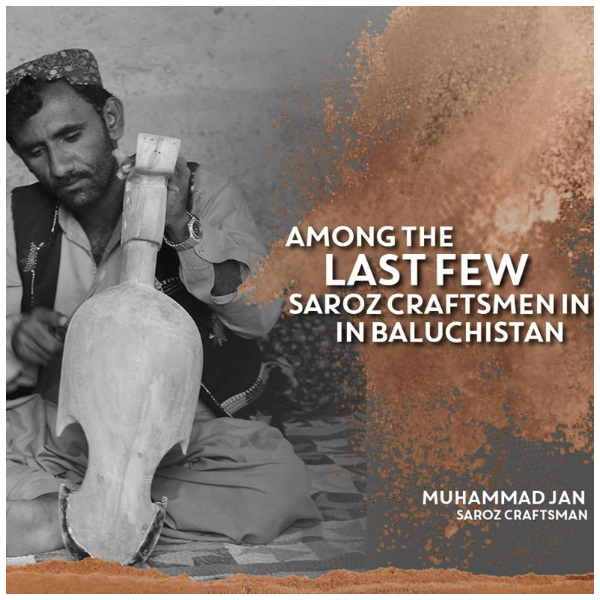

The film then travels to Balochistan where we are introduced to Sachu Khan who is a legendary Saroz folk artist of Pakistan. As of right now, he is the only Saroz instrumentalist and fighting a battle against heart disease. As the last craftsman of this instrument, Muhammad Jan narrates his day-to-day struggle as the demand for the instrument is meagre.

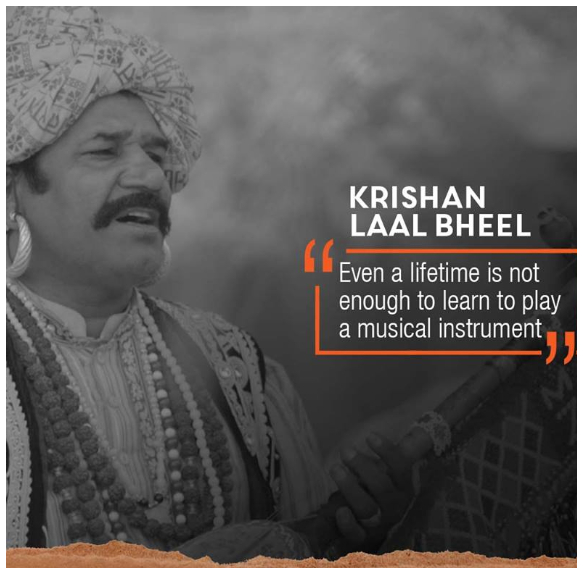

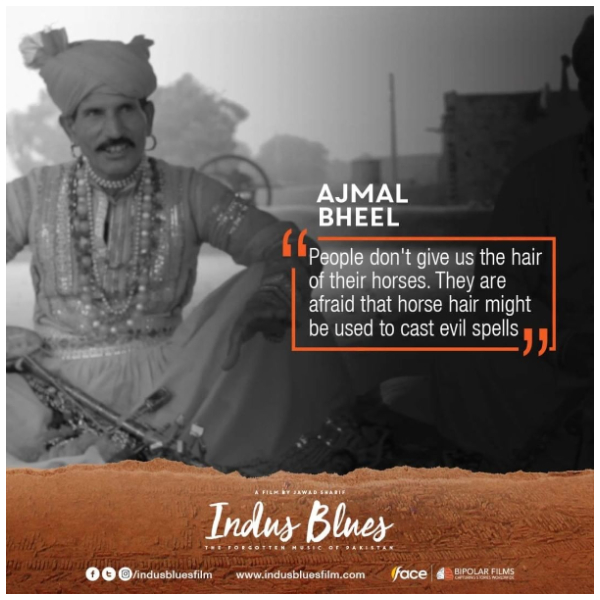

From Rahimyar Khan, the Bhakti troupe of the Cholistan tribe comprises Krishan Laal Bheel and his protégé Ajmal Laal Bheel. Both of them create and play the Raanti instrument and struggle to find material for crafting. “The instrument’s string is made from horsehair, but people refuse to give us horsehair as they fear we might do black magic using them,” Ajmal revealed. The duo is the only player and crafter of Raanti in Pakistan. The tribe is barely making ends meet with their craft and struggling to earn bread and butter.

The Raanti player from Rahimyar Khan

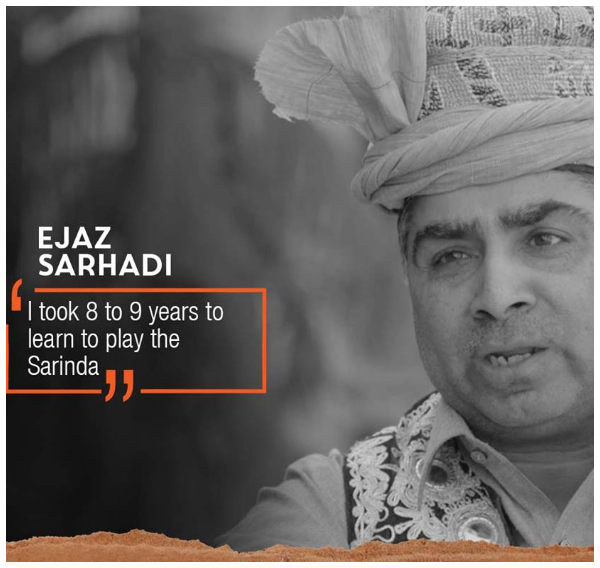

Entering the scenic Peshawar, Ejaz Sarhadi’s family is credited for popularizing Sarinda in Pakistan and United India. Even though he is the only Sarinda player left in the country, his son opted to learn the Saxophone instead. In the documentary, the artisan shared that his mother supported him and in fact, even taught him how to improve his skills.

Sarinda player from Peshawar

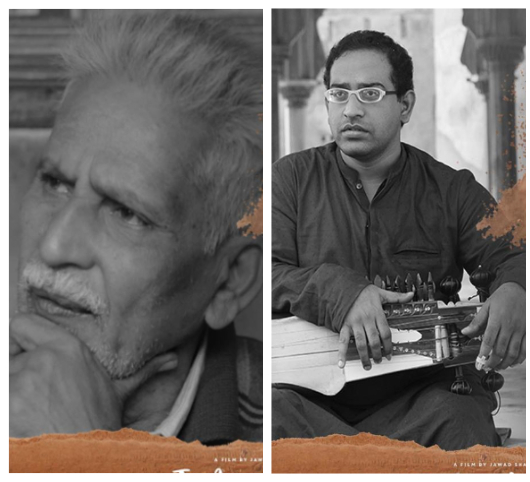

One of the most prominent Sarangi players in Pakistan, Zohaib Hassan plays the instrument which has 34 strings, making it the world’s most difficult to play. It was long linked with the classical dance of Shahi Mohalla, Lahore which was outlawed by General Zia-ul-Haq’s regime.

“The Sarangi players have not allowed their children to pursue a career of playing the instrument which is a huge loss for our country,” Zohaib expressed. Awarded the Presidential Pride of Performance Award, Ustad Ziauddin is the only Sarangi craftsman in the country. He believes that music has been outlawed by extremists as there has been no evidence to prove from Holy Scriptures that is prohibited in Islam.

Left: Ustad Ziauddin, Right: Zohaib Hassan

The 76-minute documentary creates awareness and is likely to stay with you, forcing you to think about how you can contribute to the cause. Music which continues to connect us globally and is an integral part of our heritage is breathing its last right in front of us, while we remain engaged in frivolous activities, oblivious of the reality of so many talented veterans around us. Jawad and Arieb have created a masterpiece which is not only shot in an alluring fashion but also sheds light on the ongoing tragedy of dying Pakistani folk music.