Sabaat stands out as a television drama and it touches upon several different themes, some subtle, some directly embedded within its powerful screenplay by Kashif Anwar. Whilst the Urdu drama title itself translates to perpetuity, it’s worth mentioning the powerful aspects that other television producers and writers could learn from whilst concocting or evaluating a script for global consumption and wholesome entertainment.

Here are the top five things that Sabaat has mastered:

1. Inter-generational relationships

Pakistani television dramas are famous for being centred on a certain type of linear romantic relationship, stemming from a marriage with its shadows falling across generations (Sadqay Tumhare), enlivened by some extra-marital masala (Meray Paas Tum Ho). Sabaat breathes fresh air into highlighting the complicated relationship between a grand-daughter and her maternal grandmother (Azra Mansoor as Naani). It is worth noticing that Miraal’s (Sarah Khan) mother and maternal grandmother live together and share a close bond. Miraal has a conflictual relationship with her grandmother whilst she is alive, but after Naani’s death, she develops a different perspective about what her grandmother used to chide her for, once she begins to read Naani’s journal. It then begins to impact her psychologically through dreams and hallucinations. A key dynamical and focal relationship is the ongoing contentious relationship shared between Miraal and her grandmother’s spirit.

It’s interesting to watch the calm, understanding and the affectionate dynamic between Anaya (Mawra Hocane) and her parents; they dote upon their only daughter and adore her, but also make room for her own viewpoint, changing temperament, and her goals and aspirations. Whilst Hassan may share an entirely different dynamic with his parents, Sabaat ensures that everyone has their voices properly and extensively heard by their parents, whether it is Anaya, Hassan or even Miraal. This is a refreshing change from most dramas (Ghalati, Khaas and Pyaar Ke Sadqay, Sadqay Tumhare) in which parents blatantly dismiss and disregard what their children desire and aim for in life.

2. Change is the only constant

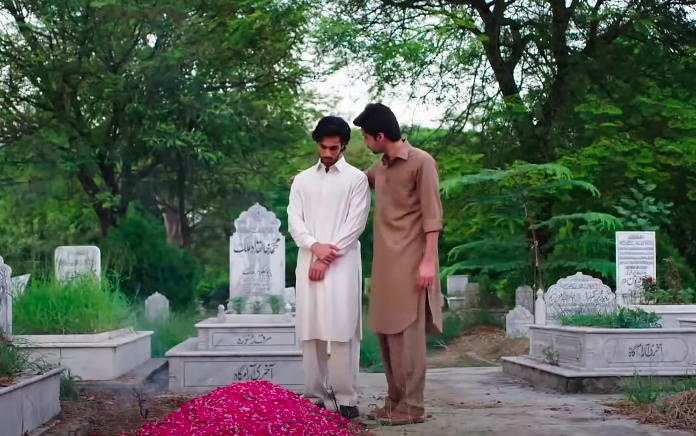

Through Hassan (Ameer Gilani), his mother (Laila Zuberi) and his Naani’s character, there are several instances where the insignificance of chasing wealth and unwarranted arrogance over physical beauty i.e. ‘takabbur’ is questioned. It makes one think about the meaningless superficial barometer with which society measures people’s worth. There is a beautifully shot scene in the third episode, at the graveyard when Hassan speaks to his friend after offering fatiha for his grandmother, and he questions mortality by musing; ‘What are we actually? Our body is like a network, even if a single cell gets damaged, our life could end’. Similarly, Miraal’s single strand of grey hair which she frantically covers with ebony mascara, reminds us that ephemeral youth and transient beauty will eventually fade and that nothing lasts forever.

3. Redefining attraction

Almost every drama has the young desirable woman entering the frame with perfect blow-dried hair, with the wind blowing her already lustrous hairdo, highlighting her stunning entrance into the drama’s plot. This then becomes the basis for the opposite sex to be attracted to her, fuelling love at first sight. Sabaat, on the other hand, initiates a romance with contention, via a harsh and hard-hitting argument that Anaya and Hassan have. This gives way to the rarely pursued plot twist: the conflict that catalyzes change. Hassan’s interest in Anaya as a potential partner stems not from her external physical appearance but through the beauty emitted by her intellect, presence, academic brilliance, and her firm, yet pleasant and forthcoming persona.

4. The art of subtlety

Sabaat proves to us that you do not need to yell to be heard. Poetic dialogue, subtle yet crass commentary, crude condescending remarks, and the sarcastic statements made by Mr Fareed’s (Moazzam Ali Khan) and Miraal’s character are enough to send a chill down your spine. Two ever-lasting, calm insults that will continue to haunt you: “Deemak keh rahi hai ke lakri mera rizq hai, mujhe na maro†(Mr Fareed, Episode 4) and “Humne apne problems solve karne ke liye tum jese kayi naukar rakhein hain apne ghar par [We often keep servants like you in our home to solve our problems].†(Miraal, Episode 3).

The show also reminds us that death, grief and mourning for a loved one can be expressed with quietude. Miraal doesn’t shed a single tear when her grandmother passes away before her very eyes, and yet her grief is evident just through the intensity of her facial expression. Despite Naani’s close bond with the family, a solemn prayer gathering and everyone reminiscing about her in their own way are enough to convey the impact that her (Naani’s) sudden departure has had on each family member. We are spared of loud jarring background music and chest-beating wailing, which is mostly inflicted on women to carry through.

5. The portrayal of women & their camaraderie

It’s rare for a drama to pass the Bechdel test (a scene in which two women talk to each other about something other than a man), but Sabaat does so with flying colours. Most dramas depict college-educated women and college going women (Dil Ruba, Maat, Raaz e Ulfat etc) all talking to each other about men, marriage and marital problems, or at the most, their conversations expand to shopping sagas. Whilst there is nothing dreadfully wrong with this, there definitely needs to be a more nuanced treatment for the portrayal of young college-educated women in Pakistani dramas.

Another unnecessary trend dramas are latching onto are infidelity (Jhooti, Meray Paas Tum Ho, Khasaara) and sister rivalry (Kashf, Yaariyaan, Thora Sa Haq, Mere Harjai, Madiha aur Maliha, Maat, Yahan Pyar Nahi Hai).

Sabaat, takes a clear steer from these two formulaic approaches and portrays its women protagonists with substance. Anaya is an engineering student, who builds an eco-friendly factory model with filters to prevent industrial air pollution, and wins a science competition. She and her friends actually study at a library, prepare for exams and support each other in times of distress. Anaya applies for jobs, commutes by bus to attend college and is seen spear-heading an anti-harassment campaign.

Even Miraal, with her evident shades of grey, doesn’t just sit at home and boss people around, she actually goes to work, goes to court to represent her family’s firm and is keen to learn more about her father’s business. This should inspire young viewers, especially women to support their fellow classmates and foster camaraderie in lieu of spiteful competitiveness for male attention.