The July sun is beating down on Karachi, where Osman Yousefzada is producing part of the work for his upcoming exhibition. The British-Pakistani artist is dressed in a blue kurta, a white straight pajama, and black platform sandals. His speech is unhurried and peppered with pauses that are partly contemplative and partly due to exhaustion.

For the past six months, Osman has been visiting Pakistan to work on the production of his artwork. In Karachi, he’s been spending his days flitting between various workshops all over the city. From Karachi, he’s been taking daytrips to Lahore. This is only part of the operation. There are also pieces being made in the United Kingdom and Venice. The work has come to a frenzied pace over the last few weeks as Osman’s exhibition draws nearer. Now, on the eve of his departure from Pakistan, he is racing against time to ensure that the final pieces are ready and packed before his flight.

The exhibition in question is titled What Is Seen, What Is Not and is scheduled to open in a museum that is recognizable to even the most casual consumer of art: The Victoria and Albert. For Osman, this is only the latest recognition in an already celebrated career. The interdisciplinary artist has designed clothes worn by Lady Gaga, Beyoncé, and Taylor Swift, to name a few – but he’s quick to correct when referred to as a fashion designer, a label he doesn’t identify with.

Osman’s art has been shown across the world, in the United States, Italy, Belgium, Bangladesh, and all over the United Kingdom. He famously wrapped an Infinity Pattern around the Selfridges in Birmingham, where he was brought up.

Osman poses in front of his Infinity Pattern in Birmingham

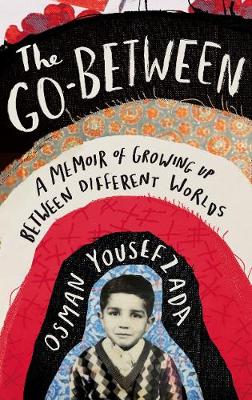

Osman’s by-line has appeared in the Vogue, The New York Times, The Guardian, and on the cover of his autobiographical novel The Go-Between. A thinker by nature, Osman is also recognized as an academic. He holds degrees from Cambridge, Central St. Martins, and SOAS. As a visiting professor, he has taught students at the Birmingham School of Art and University of the Arts London, and is a research practitioner with an insatiable appetite for exploring the intersectionality of politics and culture.

At the Indus Valley School of Art and Architecture (IVS), a faculty member remarks at Osman’s seemingly inexhaustible reserves of energy. Over the past few weeks, IVS’s textile department has been facilitating part of Osman’s production process and has gotten a front-row seat to his process. He flies off to Lahore in the morning, is back in Karachi at night, is in Korangi the next morning, and at IVS by the afternoon. All the while, he is overseeing the production of his pieces, managing the procurement of necessary materials, and fitting in interviews with the press.

During this interview, he is interrupted often. A voice note from an associate asking him whether he wants net in red or green, a phone call from another informing him they’re at IVS’s gate. Osman Yousefzada is clearly tired. Yet, there is not an ounce of resignation in him. Every phone call is answered with a cheerful greeting and every decision is tackled head-on.

Osman has authored an autobiographical novel about his childhood in the United Kingdom

It seems, then, that Osman’s secret is a simple one. Some people work to the point of exhaustion, Osman works beyond it. He’s driven by the kind of urgency that comes from critically engaging with the world, from being filled with observations and thoughts that demand expression. It’s clear that his mind works in a sort of overdrive. He weaves between topics, speaking about spatial boundaries in one minute, talking about migration in the next, touching on climate change somewhere in between. His usually slow drawl speeds up when he latches onto a train of thought. He becomes more animated, talking without pause till he’s managed to voice the entire length and breadth of an idea.

Of spaces and boundaries

Conceptually laden, Osman’s work reflects his rich intellectual landscape. The Infinity Pattern in Birmingham – an unbroken, tessellating pattern of pink and black shapes – represented a world without boundaries and the endless possibilities that arise from intersection. At the Lahore Biennale 2020, Osman famously constructed the inside of a grave. Surrounded by a black curtain, the installation offered viewers the chance to walk through the grave while contemplating themes of death and grief. Notably, the installation – titled No Exit – enabled women to experience the grave in a way that they are not traditionally allowed to in Islamic burial rituals.

In Osman’s art, space is transformed from the site of an artwork to the medium itself. In 2018, Osman recreated his mother’s room at the Ikon Gallery in Birmingham. Called A Migrant’s Room of Her Own, the installation was sparsely decorated with a bed, a dressing table, and a tall structure (presumably a cupboard) covered in black cloth. Placed throughout the room were various items, perpetually packed: a stack of cooking pots covered in plastic wrap, potlian (bundles) of black plastic, and large checkered storage bags filled with unnamed items.

In 2020, Osman wrapped his Infinity Pattern around the Selfridges in Birmingham

When Osman took his mother to see the installation, the first thing she asked was who sleeps in the bed. The very question is evidence of the layers of meaning created by his work. “I put this semblance her room in a white gallery space because I could. I had the privilege to do that, someone allowed me to. But she couldn’t fathom that. It’s still a functional piece of furniture so, for her, the question was why should there be a bed which doesn’t have an owner when there are people in this world who are homeless.”

A Migrant’s Room of Her Own is emblematic of Osman’s body of work in how it simultaneously manages to touch upon a variety of issues. There is the apparent theme of migration that is given away by the title. “It’s this idea of codes, that you’re more successful as an immigrant if you have a set of codes that is universal. You come from a space that is paraya and ajnabi, and you bring that space with you to a white society. You sort out your subsistence, find a means of income and roof to put over your head, and then you build a new space with elements of the Other space you’re coming from,” explains Osman.

In 2018, Osman recreated his mother’s bedroom in an installation titled A Migrant’s Room of Her Own

Born to Afghan-Pakistani parents, Osman is a first-generation immigrant who grew up in Birmingham in the 1980s. The city boasts a significant population of South Asian Muslims who maintain conservative social norms. Osman’s sisters were not allowed to pursue an education, the women around him were purdah nasheen, and there were strict spatial boundaries between the feminine and the masculine. Growing up, Osman observed how these traditions interacted with the customs of English society. He found himself drawn towards the world of the feminine, which he found to be softer and more expressive, running parallel to the world of men.

It is these early observations of gendered segregation that sparked Osman’s interest in spaces and boundaries. “Despite being very segregated, women in South Asian migrant communities somehow cope. In fact, not only do they cope, but they also thrive. They created parallel economies, they stay together and help each other, and create deep bonds. So my work is about spaces, the spaces of men and the spaces of women. A child is not yet a sexualized being so as a child I was allowed to pass through these boundaries freely.”

At the Lahore Biennale, Osman constructed a grave, inviting visitors to contemplate on the site of death and mourning

Osman is fascinated with the subjectivity of space. “If you’re looking at an object from one angle and I’m looking at it from another, we see a world of difference,” he muses. He is also interested in the many ways in which space and boundaries assert themselves. “Women had agency in certain rooms. Hence the potlian, where they covered belongings and put them away. The packaging was a sign, a barrier. Someone had to untie that knot to be able to go inside the potli, to find out what the woman had stored away. It was the woman’s way of saying, ‘This is my space, keep out of it,’” explains Osman.

Even Osman’s identity as an artist is an attempt to break down boundaries. He prefers to be called an interdisciplinary artist rather than a multidisciplinary one. “It’s the same conversations across different media,” he says, “I’m anti hyper specialization. I think anyone who’s a culture producer should be more interdisciplinary. The intersections is where the interesting work is created when borders are broken down, because those borders are where the social injustice is.”

The art

Visitors to What Is Seen, What Is Not will be greeted with work that is as thematically rich as the rest of Osman’s work. Commissioned by the British Council, in collaboration with the Victoria and Albert Museum and The Pakistan High Commission, the exhibition will be unveiled later this month. It is part of British Council’s festival Pakistan/UK: New Perspective, which will celebrate Pakistan’s 75th anniversary.

What Is Seen, What Is Not is a series of spatial interventions, with site-specific work displayed over three spaces in various mediums. Visitors will first encounter Osman’s work as they enter the museum’s Dome gallery. Here they will be greeted by a series of hanging tapestries. The banners will show figures in motion, appliqued onto backgrounds embellished with metallic thread, colorful dye, and other woven decoration. The figures will evoke the protection symbolized by talismanic symbols in the various cultures of the Indus Valley, such as the Priest King of Mohenjo-Daro. They will invite viewers to contemplate on South Asia’s rich and complex cultural history.

Osman works on one of the tapestries for his exhibition at the V&A

“Actually, I’ve been doing those figures for several years now,” explains Osman. “At first, they were very much from the Falnama, they were inspired by the ghouls and demons in that text. In Pakistan, a couple of people pointed out that they look like figurines from Mohenjo-daro and I thought that was perfect. I’ve been doing this stuff subconsciously and they’ve ended up being reminiscent of Mohenjo-daro.”

From Mohenjo-daro, visitors will be led to the sculptures gallery where they will be greeted by an installation reminiscent of the makeshift shrines of Pakistan. A simple wooden structure, held together by rope, will display a series of potlian cast in glass, clay, or woven in rich textiles. The packages will contain and have the appearance of containing everyday household items like cooking pots and vessels. This will evoke the theme of migration that seems to run like a thread through most of Osman’s work.

Much like a shrine, the structure will invite visitors to contemplate, specifically on the totem like objects it holds. They will be reminded of the ways in which migrants carry their most cherished possessions, as they travel from one place to another, displaced by sociopolitical and economic conditions. “I actually wanted to package some of the objects in the museum and they wouldn’t let me,” laughs Osman, “Because there’s this question of who owns what in museums and how artifacts get to these spaces.”

Potlian (packages) of household items are a repeated motif in Osman’s work

From the ‘shrine’, visitors will be directed towards the John Madejeski Garden, which Osman will have transformed into a space for communal contemplation. Charpai [beds] of various sizes will be placed in clusters across the grass, inviting visitors to sit together. Each charpai will be made using different weaving techniques, reminding visitors of the diversity of Pakistan’s textile heritage.

Morah stools will be stacked in a cubed arrangement, available for visitors to use. As more visitors will make use of the stools, the cubed arrangement may grow smaller and eventually wither away. Conversely, should they choose to, visitors my reposition them into new arrangements. Hence the stools will be constantly moved, repeatedly unpacked and packed into transitory and communal arrangements.

The garden installation will be centered around a wooden boat, built at Ibrahim Hyderi and typical of the vessels used to navigate through coastal mangroves. The boat will be moored on land to symbolize the erosion of natural environments and the danger posed by climate change to for water-dependent communities. Above the boat will hang a banner on a wooden frame and adorned with emblems and objects typically found in Pakistan’s shrines.

“The mangrove boat was actually quite key to me, “says Osman, “I remember coming to Pakistan as a kid and the Indus River was massive. There are stories that before the dam wars, it was very much the boundary between Greater Persia and Greater India. My heart breaks over the water issue in Pakistan,” says Osman, “It’s a country that contributes to one per cent of global greenhouse emissions but ends up being the fifth most vulnerable country to climate change.”

Osman Yusefzada oversees craftsmen working on his tapestires

It’s no wonder, then, that our artist is tired on this sweltering July afternoon on the eve of his departure from Pakistan. It’s no small task to conceptualize and design work that spans over millennia of cultural history, weaving through layers of meaning while visiting multiple civilizations.

Exceedingly modest, Osman is nonchalant about the magnitude of his own work. But even he can’t deny the significance of this exhibition. “It’s the first time that Pakistan, instead of being drowned in the conversation of South Asia, will be represented at the V&A and it’s quite a big thing,” he says, “There’s a lot of meaning but, hopefully, the work is beautiful and it’s aesthetically pleasing.”

This platform exceeded my expectations with robust security and quick deposits.

I personally find that riley here — I’ve tried checking analytics and the accurate charts impressed me.

The cross-chain transfers process is simple and the scalable features makes it even better. I moved funds across chains without a problem.

I personally find that fast onboarding, stable performance, and a team that actually cares. The mobile app makes daily use simple.

I personally find that the trading process is simple and the clear transparency makes it even better. My withdrawals were always smooth.

?Cheers to every wanderer of destiny !

О— ОґО·ОјОїП„О№ОєПЊП„О·П„О± П„П‰ОЅ online casino ПѓП„О·ОЅ ОµО»О»О¬ОґО± ОП‡ОµО№ ПѓО·ОјОµО№ПЋПѓОµО№ ПЃО±ОіОґО±ОЇО± О±ПЌОѕО·ПѓО· П„О± П„ОµО»ОµП…П„О±ОЇО± П‡ПЃПЊОЅО№О±. [url=http://casinoonlinegreek.com/#][/url]. О‘ПЃОєОµП„ОїОЇ ПЂО±ОЇОєП„ОµП‚ ПЂПЃОїП„О№ОјОїПЌОЅ О±П…П„ОП‚ П„О№П‚ ПЂО»О±П„П†ПЊПЃОјОµП‚ О»ПЊОіП‰ П„О·П‚ О¬ОЅОµПѓО·П‚ ОєО±О№ П„О·П‚ ПЂОїО№ОєО№О»ОЇО±П‚ ПЂО±О№П‡ОЅО№ОґО№ПЋОЅ ПЂОїП… ПЂПЃОїПѓП†ОПЃОїП…ОЅ. ОњОµ П„О·ОЅ ОєО±О»О® ОµПЂО№О»ОїОіО®, ОјПЂОїПЃОµОЇП„Оµ ОЅО± О±ПЂОїО»О±ПЌПѓОµП„Оµ П„О·ОЅ ОµОјПЂОµО№ПЃОЇО± П„ОїП… П„О¶ПЊОіОїП… О±ПЂПЊ П„О·ОЅ О¬ОЅОµПѓО· П„ОїП… ПѓПЂО№П„О№ОїПЌ ПѓО±П‚.

Choosing a kazino online with a solid reputation can provide a sense of security for players. A well-reviewed platform with a track record of fair play and timely payouts is more likely to provide a positive gaming experience. Doing your research prior to participating can pay off remarkably.

О“ОЅП‰ПЃОЇПѓП„Оµ П„О± ПЂО№Ої ОґО·ОјОїП†О№О»О® online casino ПѓП„О·ОЅ О•О»О»О¬ОґО± П„ОїП… 2023 – http://casinoonlinegreek.com/

?May luck accompany you while you let destiny grant you intense surprising victories !

I personally find that i switched from another service because of the quick deposits and trustworthy service.

I personally find that i was skeptical, but after since launch of providing liquidity, the seamless withdrawals convinced me. Definitely recommend to anyone in crypto.

I personally find that i value the clear transparency and stable performance. This site is reliable.

The testing new tokens process is simple and the wide token selection makes it even better.

I value the scalable features and trustworthy service. This site is reliable.

The site is easy to use and the intuitive UI keeps me coming back. The dashboard gives a complete view of my holdings.

I personally find that the best choice I made for cross-chain transfers. Smooth and responsive team.

I personally find that corey here — I’ve tried using the API and the useful analytics impressed me.

I personally find that i value the wide token selection and stable performance. This site is reliable.

I value the wide token selection and clear transparency. This site is reliable.

?Levantemos nuestros brindis por cada forjador de la prosperidad !

Los casinos sin registro a menudo cuentan con una amplia variedad de proveedores de juegos. casinos sin registro. Esto asegura que la calidad de los juegos sea alta. La diversidad de opciones tambiГ©n significa que siempre hay algo nuevo para probar.

Los casinos online sin registro suelen ofrecer generosos bonos de bienvenida. Estos incentivos son ideales para captar la atenciГіn de nuevos jugadores y maximizar su diversiГіn. Con un poco de suerte, podrГas comenzar tu aventura con un buen saldo adicional.

Mejores casinos online sin registro para maximizar tu diversiГіn

?Que la fortuna avance contigo con celebraciones eternas jugadas victoriosas !

I’ve been using it for several months for exploring governance, and the accurate charts stands out.

I’ve been using it for over two years for providing liquidity, and the trustworthy service stands out.

I switched from another service because of the accurate charts and clear transparency.

Hunter here — I’ve tried portfolio tracking and the great support impressed me.

I personally find that i was skeptical, but after a few days of providing liquidity, the reliable uptime convinced me. The updates are frequent and clear.

The using the bridge tools are responsive team and accurate charts. The mobile app makes daily use simple.

I personally find that i was skeptical, but after several months of exploring governance, the clear transparency convinced me. Perfect for both new and experienced traders.