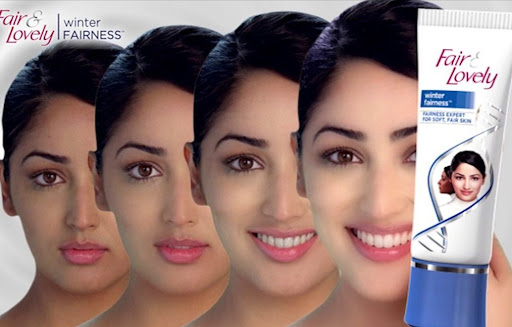

This week, in nothing short of a historical move, Unilever Pakistan announced that it would be getting rid of the word ‘fair’ in its highest selling beauty product, Fair & Lovely. For years there have been efforts to change the cream’s perception of being a fairness cream to one that is more of a sun block, a beauty balm (BB cream), a skincare essential and basically anything to counter its association with being fair. Nothing has worked, primarily because the words ‘whitening’ and ‘brightening’ have figured hugely in campaigns and secondly, the ads have ad nauseum associated being fair with success in marriage, career and life in general. Before and after pictures of women’s faces and their shades of fairness are ingrained in our memory as keys to success.

The problem and its solution is much graver than a fairness cream and its name. In the past one month, we’ve seen the revolutionary Black Lives Matter movement rise in the USA after the murder of George Floyd and countless other Afro Americans who have suffered various degrees of victimization because of the colour of their skin. So the seemingly innocent existence of a fairness product cannot be isolated as just that; it stems from centuries of colourism, racism and perpetuates the association of white skin with superiority.

The model is shown to be progressively happier as she gets progressively fairer.

Things are changing.

Mega brand Johnson and Johnson was the first to take a step in the right direction and admit that its product lines, Neutrogena Fine Fairness and Clear Fairness by Clean & Clear – sold only in Asia and the Middle East – gave out the wrong message. This came after harsh criticism against brands that gave press statements in solidarity with the Black Movement but then continued to manufacture and market products that strongly suggested that you’d be better off with fairer skin.

“Conversations over the past few weeks highlighted that some product names or claims on our Neutrogena and Clean & Clear dark-spot reducer products represent fairness or white as better than your own unique skin tone,†the company said in a statement. “This was never our intention — healthy skin is beautiful skin.â€

Band-Aid, also owned by Johnson & Johnson, announced it would start selling bandages meant to match different skin tones.

“We stand in solidarity with our Black colleagues, collaborators and community in the fight against racism, violence and injustice,†Band-Aid said in an Instagram post. “We are committed to launching a range of bandages in light, medium and deep shades of Brown and Black skin tones that embrace the beauty of diverse skin. We are dedicated to inclusivity and providing the best healing solutions, better representing you.â€

Band Aid now comes in a range of skin tones to be more inclusive.

Black Lives Matter kickstarted the conversation and brands with a conscience have started rethinking their marketing strategies. Quaker Oats, for example, announced the removal of the character ‘Aunt Jemima’ from its pancake mix and syrup brand after admitting that the image of a grinning black woman was based on a racial stereotype. The same applied to household products like Cream of Wheat, Uncle Ben’s Rice and Mrs Butterworth, all widely available in the USA.

It was only a matter of time and an aggressive petition calling on Unilever to stop selling Fair & Lovely that the cream would pause and rethink.

“This product has built upon, perpetuated and benefited from internalized racism and promotes anti-blackness sentiments amongst all its consumers,†the petition said, according to the New York Times. In South Asia and the Far East, that internalized racism came not from slavery but colonialism.

It’s not just beauty products but classic literature too that has come under fire in the past one month. Two weeks ago WarnerMedia pulled off Gone With The Wind, one of the most classic books and subsequently one of the most popular movies of all times, from its streaming service. The film has now been restored, but with a disclaimer that puts it in historical context, bringing to light the horrors of slavery and racial discrimination portrayed in the film.

In the intro video, which now plays on HBO Max before the movie starts, film scholar and professor of film and media studies at University of Chicago, Jacqueline Stewart discusses “why this 1939 epic drama should be viewed in its original form, contextualized and discussed.â€

Gone With the Wind presents “the Antebellum South as a world of grace and beauty without acknowledging the brutalities of the system of chattel slavery upon which this world is based,†Stewart says, as quoted in Variety. She notes that Black cast members were not allowed to attend the movie’s premiere because of Georgia’s segregation laws. Hattie McDaniel, who was the first African-American person to ever win an Academy Award for her portrayal of the servant Mammy in the film, was not allowed to sit with the other cast members at the Oscars.

Coming back to Pakistan and Unilever’s decision to rebrand Fair & Lovely without perpetuating the fairness stereotype, one has to say that the move has to be echoed through the hugely influential entertainment industry. It’s no secret that fair skin is a weapon that opens doors for actors, actresses and models in the fashion industry. Artistes have openly spoken about the demands made on lightening their skin tone, with makeup, for the camera and various stars have evidently been lightening the colour of their skin with whitening injections. Cosmetologists will confirm that skin whitening is one of the most popular treatments at clinics in Pakistan.

Health hazards apart (ingredients in whitening creams have been proven to be carcinogenic), it’s the stereotype that associates fairness with success that has to be taken down. Let’s hope Unilever’s bold move triggers a domino effect in other brands too.